STEM Careers in Focus: Tony Hale

Dustin Miller, director of experience and innovation, returns with the fifth in his series of interviews, STEM Careers in Focus with Tony Hale. A documentary editor and filmmaker based in Brooklyn, NY, Tony’s first feature-length film, A Will for the Woods (2014, co-editor/co-director) won multiple festival awards, including two at its premiere at Full Frame, before being nationally broadcast on PBS.

Dustin Miller (DM): Tell me about your earliest memories in nature.

Tony Hale (TH)*: I grew up in Massachusetts mostly in urban and suburban settings, but time in nature forged some of my strongest memories, even if it was just under the grape vine in our yard or walks in Mount Auburn Cemetery. Thanks to my older sister Lucy*, a budding zoologist, we always had a house full of animals. I remember one Christmas my parents got her a mini fridge, which was a really big deal! With a private place to store frozen mice (something my mom would never allow in the kitchen fridge), it meant she’d finally be able to have a pet snake.

And every year in the summer my family would go to Cape Cod for a week or two. The landscapes there were magical to me. Mucky low tide marshes with fiddler crabs scurrying about, a cedar swamp, dunes, and kettle ponds that I heard were formed by glaciers. My sister even convinced me that elves lived in the woods, which felt about right given how magical everything else was and how much she knew about wildlife. I somehow always just missed them when she’d point one out to me. Apparently they don’t like to be spotted.

*Tony and Lucy are not that Tony Hale or Lucy Hale, their parents just happened to choose names that would eventually be Hollywood bound.

DM: As a kid you enjoyed mixing and editing music with friends, too. Can a speak a bit about how that led you to your work today?

TH: I credit my early music-making with providing some of the technical and artistic skills I needed to get my footing in editing. The natural world was also of interest to me, whether it was science class or summer trips outside the city, but it wasn’t as much a part of my daily life. I think an interest in ecosystems and the human stories that were connected to them did draw me to some of my early work, but my connection to conservation definitely grew deeper as I continued. I’m very happy that art and science ended up coexisting in my work life.

DM: You went to Boston College for Mathematics, so what led you to film editing?

TH: Honestly, it was having fun with friends on goofy side projects. Equipment at the time was making filmmaking more accessible than ever, but it still felt somewhat rare to have access to it, so when I was able to borrow a camera or get on a computer that had the right software, it felt like I was pulling off something special.

I didn’t study much film in college, but I did take a couple of classes. Shooting and directing seemed to be a much more common draw for others, but I loved sitting in the edit lab experimenting with the footage, manipulating what was there until it found new meaning, discovering how to breathe life into a scene. It reminds me of a Mary Shelly quote from Frankenstein: ”Invention … does not consist in creating out of void, but out of chaos.”

However, I didn’t know yet how it could be a career. I decided to work a part-time job, so that I could have time to begin cobbling together a freelance editing career. A highlight of my earliest gigs was when friend and filmmaker Lulu Wang [director of the critically acclaimed The Farewell, featuring actress Akwafina] and I ended up in a remote peninsula in Panama with a miniDV camera to make a film about sustainable fishing in exchange for room and board. After that I got some paid gigs, sometimes for things I liked and sometimes things I didn’t. And now 15 years later I’m lucky to be in a position to have projects that both can pay and that I care about.

DM: A Will for the Woods has an unusual premise for many. Can you tell us about the film?

TH: A Will for the Woods was my first feature film, and it was a really beautiful experience to work on. The film delves into the topic of green burial, which strictly speaking means burials that are 100% biodegradable and non-toxic. But interestingly, they can also be used as a conservation strategy. The idea is that if we’re using all this land for burial space, why not design it in a way that conserves and restores ecosystems instead of turning them into resource-guzzling, non-native lawns. The story of the film largely follows psychiatrist and musician Clark Wang as he plans and prepares for his own burial and manages to help save a tract of woods in North Carolina.

The film is very much about his life, the people around him, and a coming to terms with death. It’s common to refer to the concept as “a little out there”, and I think conversations around death can often bring up those feelings. However, I think it says more about our cultural perceptions, and less about the concept of green burial. Death is something we all will face, and our end-of-life decisions are going to be made one way or another. The idea of earth-to-earth is ancient, and in many ways green burial is simply a return to that tradition. My hope is that the film can help people open up to the naturalness of the cycle of life and death and its intrinsic connection to sustainability.

DM: You’ve said your work is an exercise in deep listening and context building. Which of your works has been the most impactful on you?

TH: I think it’s very impactful to hear from people living on the frontlines of ecological change, and those stories stay with me. Any film that delves deep into a subject’s life is also always very powerful. Working on A Will for the Woods was frequently a sustained meditation on mortality, and that profoundly impacted me. The story of Eduardo in Charged and that of the cyclists in Afghan Cycles taught me a ton about perseverance, gratitude, and the value of staying true to one’s self. And the activists in The Story of Plastic and the upcoming Youth v Gov give me hope and more fire to fight for a better world.

The context building I speak of is more for the audience. How does the film build a world around the subject to provide the right context to understand them. The burden can’t always be on the subject to explain their whole world. I think a film plays best when they are themselves, and the film provides enough world-building around them to support their validity and authenticity.

DM: In your blog, you’ve posted about film editor Lewis Erskine’s call to action, “Examine your privilege. Question it constantly.” Erskine talks about being a disruptor to make change happen. How do you go about disrupting?

TH: Lewis Erskine’s speech really spoke to me when I read it, especially because he’s an editor. It’s part of an important conversation around dismantling privilege, the need to examine “who is telling whose story”, and how our work can be anti-racist and anticolonial.

In documentary filmmaking, we’re often championing important causes, but that doesn’t give us a pass on critical examinations around privilege. While I hope the films I work on do things like disrupt existing narratives, the disruption Erskine calls for starts with the recognition of any privileges held by those telling the story – including the editor, who says volumes through their decisions about what makes it into an edit and what is left unsaid on the cutting room floor.

The ultimate goals, I believe, are inclusivity and equity. I don’t believe there are easy answers, but this constant examining and questioning of privilege is a good place for necessary disruption to start.

DM: Speaking of championing untold and under-told stories, what are some of the critical issues that your work has highlighted?

TH: It’s hard for me to not put the climate crisis at the top of list when discussing critical issues. Clearly, climate change is a known topic, yet the extent to which it presents an existential threat and the many facets of how it will impact us don’t make headlines as often as seems logical. I think there are a good deal of cognitive dissonance at play when it comes to grasping the scope of the issue. I believe storytelling plays a big role in getting to that tipping point within our societal psyche that we need to get to, and that really motivates me.

As far as untold and under-told stories, those are questions I like to ask about every project. What is the predictable angle of the given story, what are people (including myself) expecting this story to be, and what aspects of the story aren’t yet being told? Whose voices are missing? One clear-cut example is a piece I was honored to help put together for Avaaz about the war in Yemen, one of the worst humanitarian crises today that most Americans don’t realize our role in. (I didn’t at the time myself.) The short film was comprised of footage that was difficult to get out of the country, with messages from children in a plea to stop US logistical and military support of the Saudi attacks. They were messages almost never heard in the US.

A more nuanced example might be a story like that of Eduardo Garcia in Charged, who survived an extreme electrical injury and built back his life after losing a hand and a good deal of muscle mass. Inspirational stories about recovery from injury have been told before, and both the subjects and filmmaking team wanted to give extra focus on how winding and on-going that road of recovery is and to highlight the critical and difficult role of caregivers.

In the case of The Story of Plastic, the “untold” story is quite literally what it the documentary is about. The film focuses on how the narrative of plastic pollution has been controlled by industry to place attention on consumer responsibility and faulty waste management in developing nations, distracting the public from looking upstream to who is producing, pushing, and profiting from the material. The story we know about plastic – oceans and rivers choked with the stuff – is definitely important, but the untold story of plastic is one that also needed attention – one of fossil fuels dominating the economy, decades of marketing and political deception, and rampant environmental racism.

DM: Like other areas in the arts and cultural institutions, those producing and making decisions in filmmaking don’t represent the diversity of stories being told.

TH: Exactly. Documentary is often celebrated for its diversity of stories on screen, but we need diversity behind the scenes, too. There’s some good, much-needed discussion of this in the documentary world right now, and there’s more work to be done.

DM: What can we do to ensure diverse voices are seen and heard in arts and STEM content?

TH: Monetary support and programming decisions clearly have a major impact, and we should continue to hold institutions accountable, but we can also hold ourselves accountable as filmmakers and audience members.

Filmmakers should champion, hire, and defer work to a diversity of voices. Carefully considering who collaborates and has authorship is critical. It’s important to remember that diversity is not just about directors and who appears on screen, but also about the many, many crew members working on a film who contribute creative and technical work.

I’m encouraged by efforts such as The Karen Schmeer Fellowship’s Diversity in the Edit Room program and Brown Girl Doc Mafia’s member database, to name just a couple of examples I’m familiar with.

As audience members, we also have power. Filmmakers are already out there making beautiful work – diverse voices are saying a multitude of things about the world – and we can make efforts to seek it out. We can buy, rent, or stream their films. (And post-COVID, we can show up to screenings again.)

DM: What stories are you currently working on?

TH: I’ve recently been co-editing a film (alongside editor Lyman Smith and director Christi Cooper) that I’m really excited about [a project] called Youth v Gov, which follows the landmark climate case Juliana v. United States. From the film’s website: “YOUTH v GOV is the story of America’s youth taking on the world’s most powerful government. Since 2015, twenty-one plaintiffs, now ages 12 to 23, have been suing the U.S. government for violating their constitutional rights to life, liberty, personal safety, and property through their willful actions in creating the climate crisis they will inherit. But YOUTH v GOV is about more than just a lawsuit. It is the story of empowered youth finding their voices and fighting to protect their rights and our collective future. This is a revolution designed to hold those in power accountable for the past and responsible for a sustainable future.”

It’s really been an honor to learn more about these young people and help tell the story. I am incredibly grateful to them for their fight to secure a better and safer world for all of us.

I’m also beginning work on a very STEM-related project, 3600 Feet Beneath the Ice, which chronicles an expedition to explore one of Antarctica’s recently discovered subglacial lakes. Buried under over a kilometer of ice, the liquid lake holds secrets about life in the most remote places on Earth, as well as potential clues from past climates about where our current climate may be headed.

DM: At times, your films, such as the man denouncing female cyclists in Afghan Cycles, include opposing viewpoints. Can you share about inclusion of these voices in your work?

TH: That’s a great question, and an ethical one that director Sarah Menzies and I felt obliged to carefully consider. The question was essentially, “Is it responsible to give this person a platform for their hate speech?” He’s taking up space in a finite film that could otherwise be devoted to someone else.

But the answer for us came down to context. We had to position that scene carefully and deliberately, and be sure to clearly frame it as part of our protagonists’ experience. His presence in the film exists solely to provide a fuller picture of the reality these young women face every day when getting on a bicycle in public, specifically in this case the very real threats they face.

DM: Many would say modern technology has made filmmaking much more accessible for kids and young adults. What, would you say, hasn’t changed?

TH: It’s really amazing how much more accessible filmmaking is becoming, but what hasn’t changed is the reason we tell stories and the power they hold. There is a deeply human tradition in storytelling as a way to make sense of our reality and to attempt to derive meaning from it all. I like to remind myself that the most powerful thing in the room at any screening is going to be the human being in the audience. Regardless of the technical tools we have at our disposal, the viewer’s mind and heart is where the story will ultimately play out, and I believe that is something that hasn’t changed.

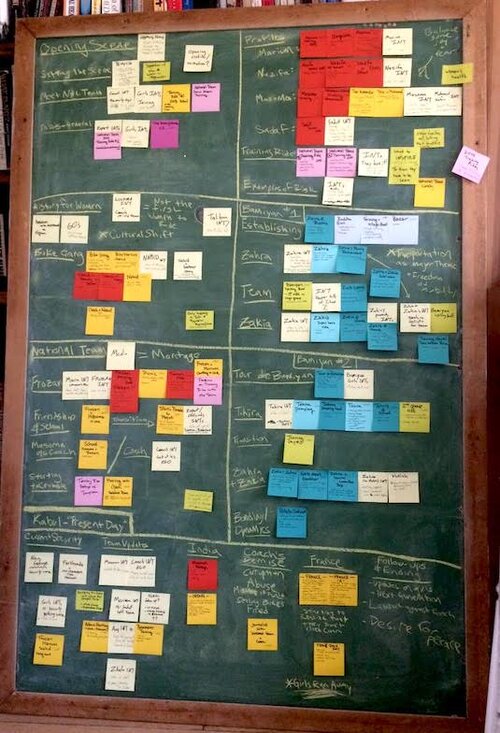

DM: The world has gone digital, yet it appears you have an affinity for sticky notes…

TH: Ha, it’s true! I do almost all my work in front of a screen and sometimes it’s just so refreshing to get tactile. I think switching it up like that is a useful way to get a new perspective. Usually after whittling hundreds of hours of footage into a manageable number of themes and scenes, taking it to the sticky notes can help me visualize all the various permutations of scenes and to see the ripple effects of moving them around. Also, for me, the sticky note phase usually means we’re approaches having a proper rough cut, which also makes it a bit celebratory.

Here’s a clip of that process when I was out in Montana working on the film Charged.

DM: Outside of your work, how do you stay connected to the world around you?

TH: Editing involves a lot of isolated time working alone. There was actually a meme going around that went something like: “Editing before quarantine vs editing after quarantine” and showed two identical pictures of an editor alone at their desk. And it rang pretty true!

So, it’s important for me to find ways to stay connected. I cherish the times I can get out into nature, and I love the woods. But I live in NYC and can’t always do that. Pre-COVID I would do the typical city things, time with friends, etc. Post-COVID, I’ve doubled down on my time spent in urban green spaces, which is one of the few things still accessible, and I am so grateful for their presence. Staying connected with friends and family, even if virtually, keeps me grounded.

Also in these last 4 years, I’ve probably been to more demonstrations than I have in the rest of my life combined, which I think is a powerful way to stay connected to the world around us.

DM: Any tips for young people on how to bring a story to life in film?

TH: Trust your instincts! Trust both the instincts that say “this is cool, this is special, let’s make something out of this” and those that say “this could be better, it’s not exactly what I want to be yet, how can I rework it?”

Embrace mistakes and learn from them.

Understand that it’s a technical and creative job. It’s OK if you’re more comfortable with one aspect of that. Every editor I’ve met has a unique mix of specific skills.

When you are editing, accept that you are inherently retelling and changing things. But stay honest to the essence of what you’re telling.

Intrigue people with mysteries that both you and they will want answers to.

Why are you making a film and not telling the story through writing or other media? Embrace the medium and remember it’s a visual and auditory experience. Visual details and good sound design that connect to all the senses bring a film to life.

“Verite” moments where the audience has time to feel like they are present in the given space, with time to breathe and observe, can go a long way.

DM: Where can we find you online?

TH: I’m on Instagram as @tonytonyhale and you can more about my work at www.tonyfilm.com, where you can also find links to watch some of these films or follow the ones that are yet to be released.

Read our previous STEM Careers in Focus interviews:

Jungle Jordan: online science personality

Alejandra Ramos Gómez: teacher/artist/activist

Jacie Hood: Rory Meyers Children’s Adventure Garden Program Manager

Rick Torres: Texas Parks & Wildlife Ranger

Written by Dustin Miller, director of experience & innovation at the Dallas Arboretum

Related Posts

Comments are closed.